I read that ludicrous line, “without historical intent…” on a museum explanatory sheet today, about…

A Person Could Go Crazy in This Dump… 49,000 Acres of Nothin’ But Scenery and Statues

We started our day as many tourists do, at the Prague castle (Prazsky Hrad). But unlike most, we walked there, which is mostly uphill and something of a trek from our hotel. There are ten different sites to see, you purchase “combo” tickets for a selection or go individually to whatever site hits your fancy. We decided six were enough.

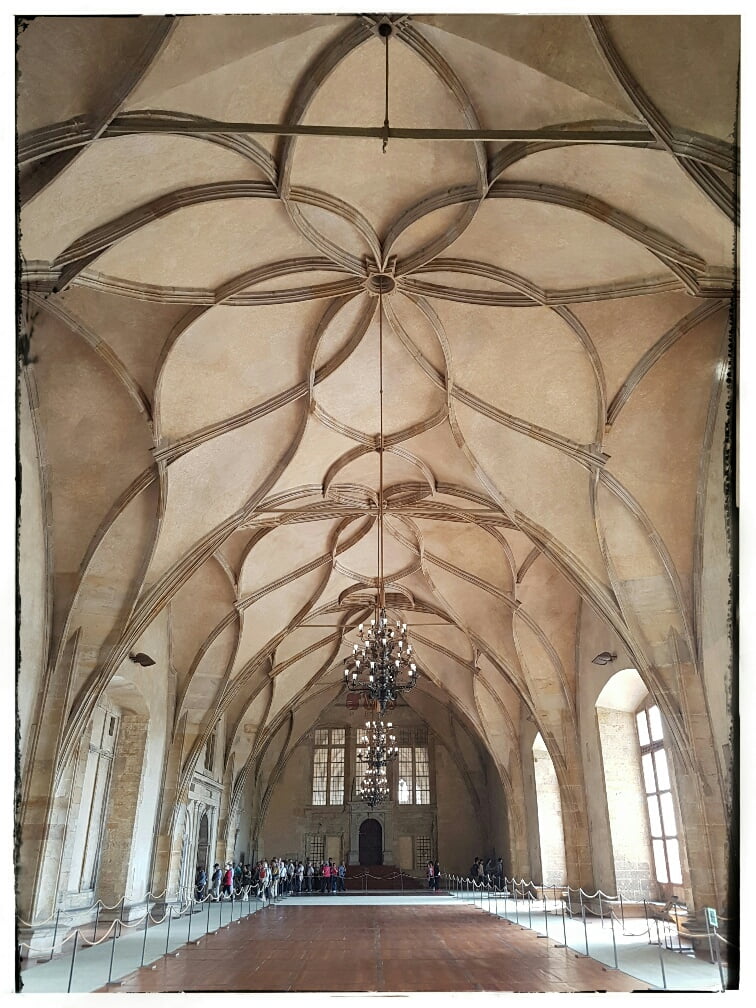

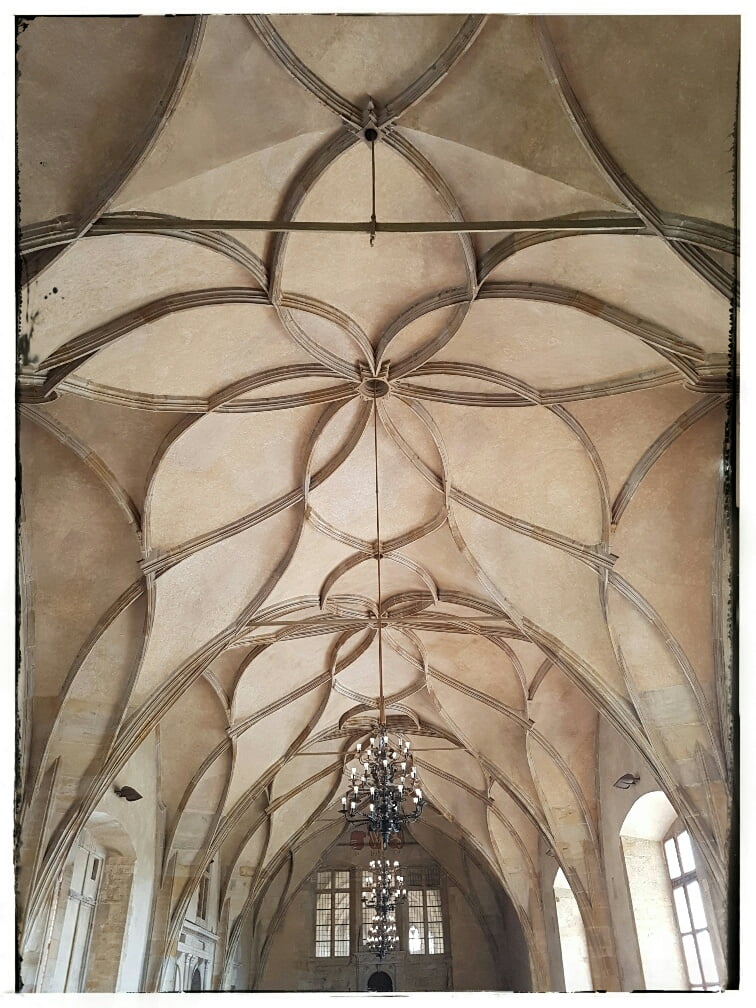

The first place we stopped at was the Old Royal Palace. The antiquity and lack of adornment were hugely appealing.

The first room you hit is the Great Hall (in Czech, Vladislav Hall). The Romanesque slash Gothic ceiling soared on forever.

Here is a (poorly shot) pic of hundreds of locals enjoying an official event in the hall–to give a remote sense of its enormity.

Next we moved into the Diet Hall, a prototype parliament with the king on the throne, the archbishop on one side, the state (aristocracy, gentry, burghers, not exactly a democracy) on the other. Took its present shape from 1563.

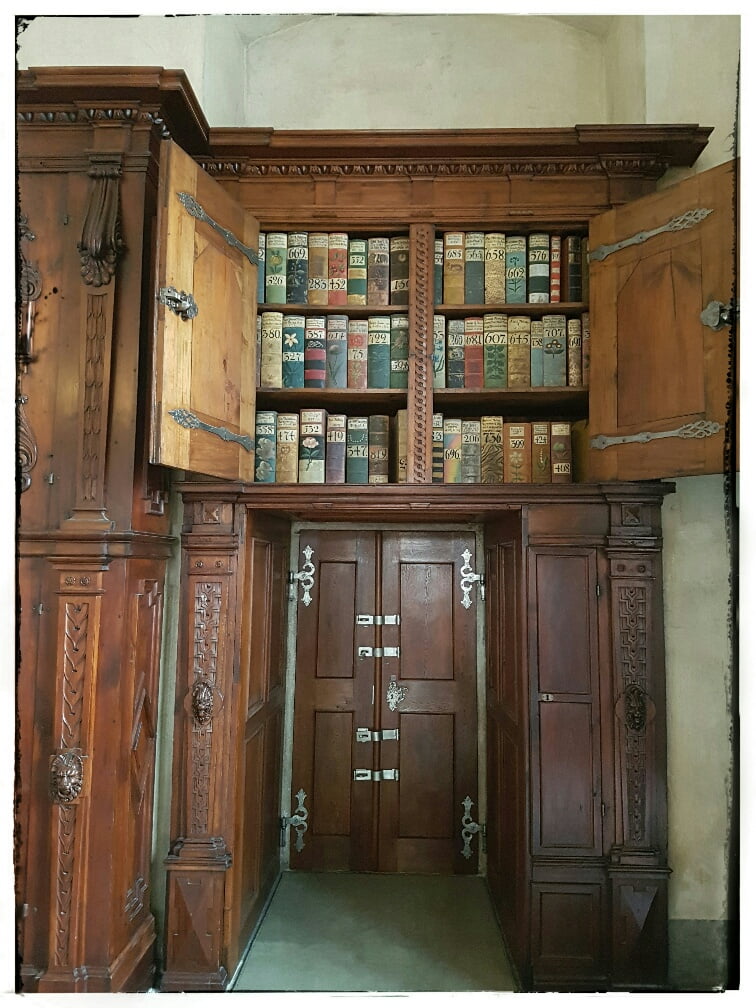

No one seemed to notice the doors, but they were one after the other exquisite.

Upstairs from the hall is is the old land rolls room.

The crests which adorned the ceiling and walls recorded significant land owners, a judge, scribe, chamberlain, etc.

Books (tomes) contained details of land ownership.

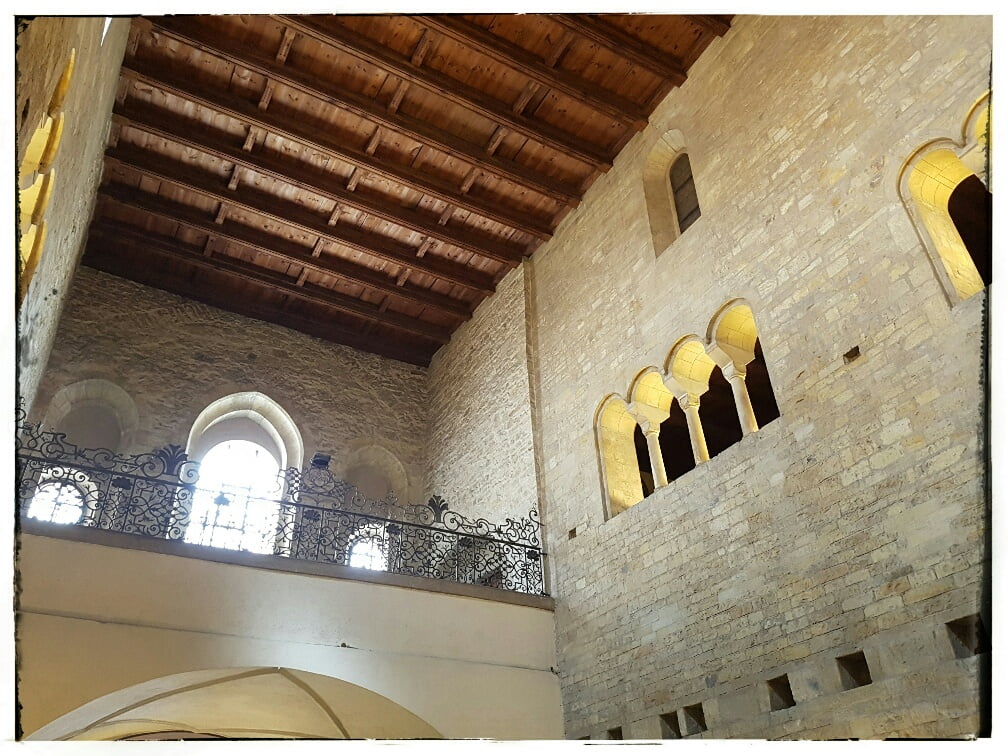

After the castle we went to the Basilica of St. George. It was founded in the 10th century. Was a nunnery in 973. The first church burnt, the current church was rebuilt in 1143. The purity of the form, the massive stone walls and flat ceiling were awesome. But not decorative enough, apparently, for most tourists.

The baroque facade and chapel which adorn the front, dating from the 1600s, fairly destroys the intent.

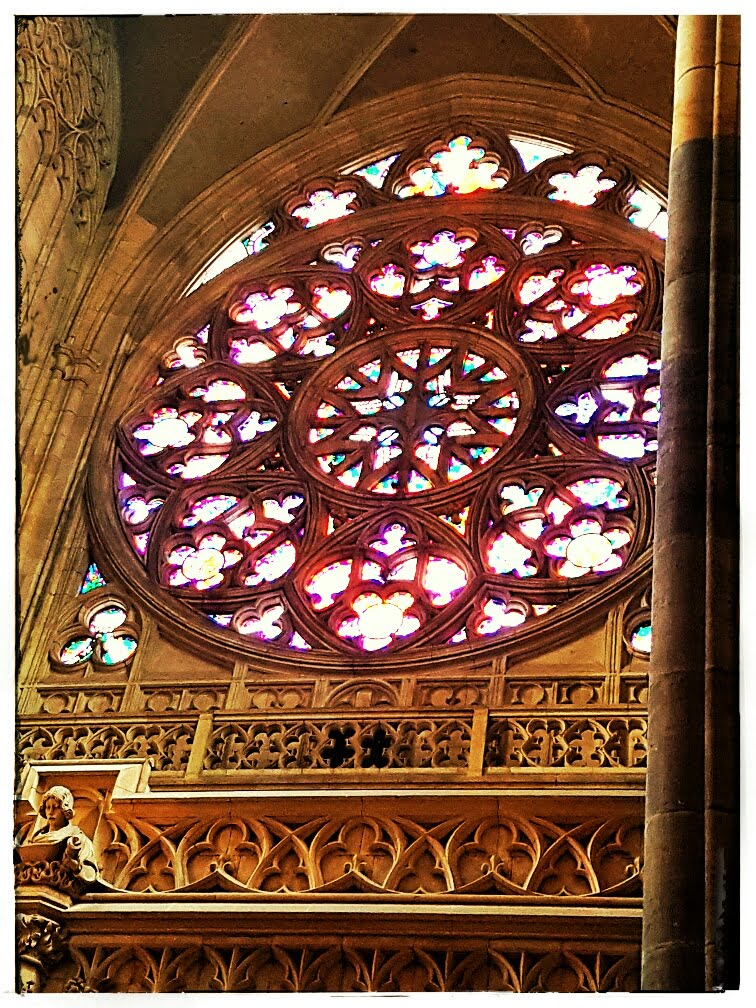

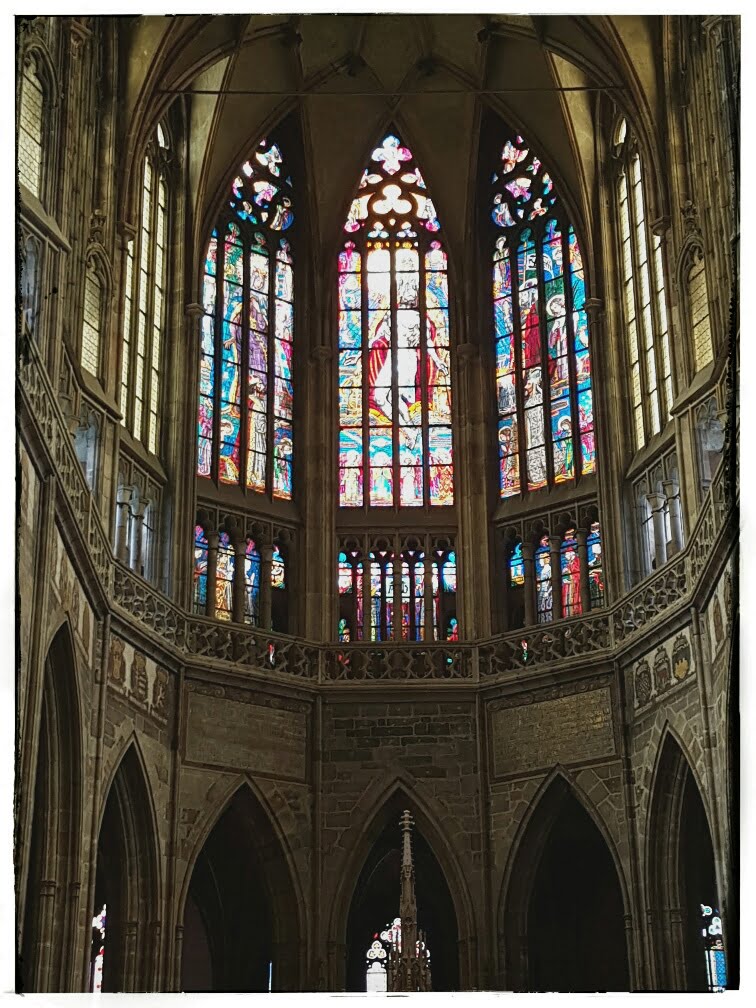

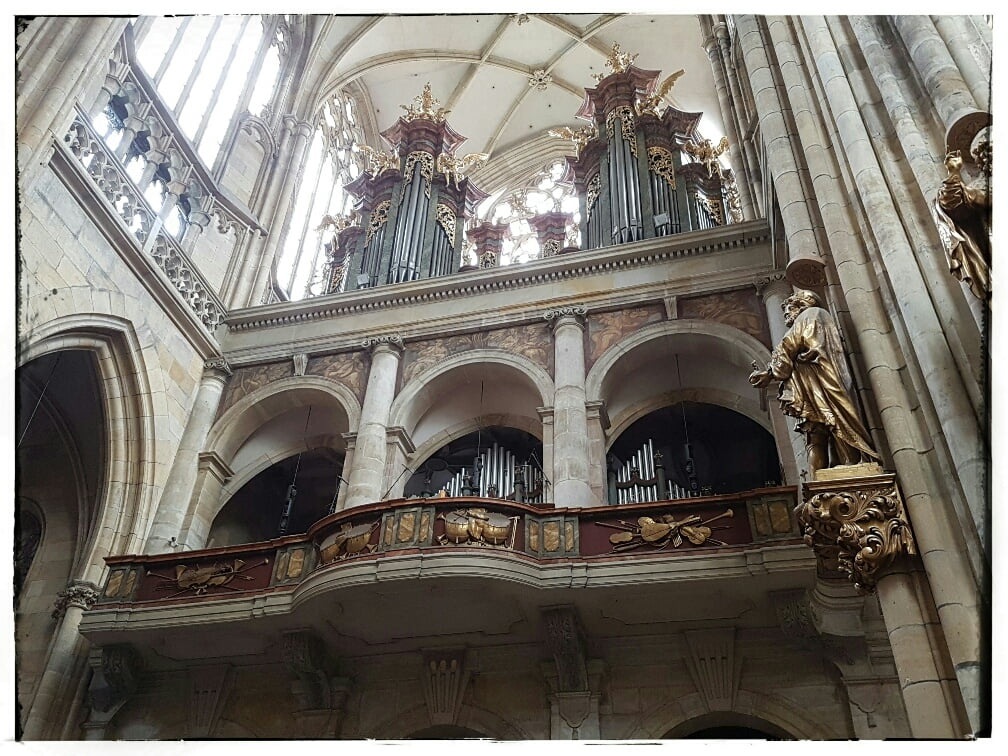

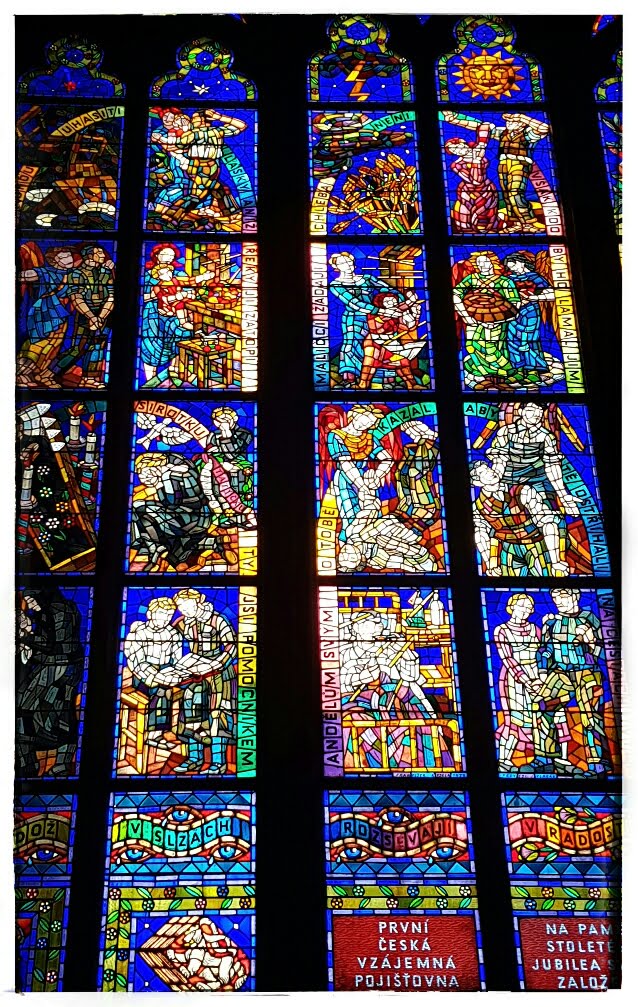

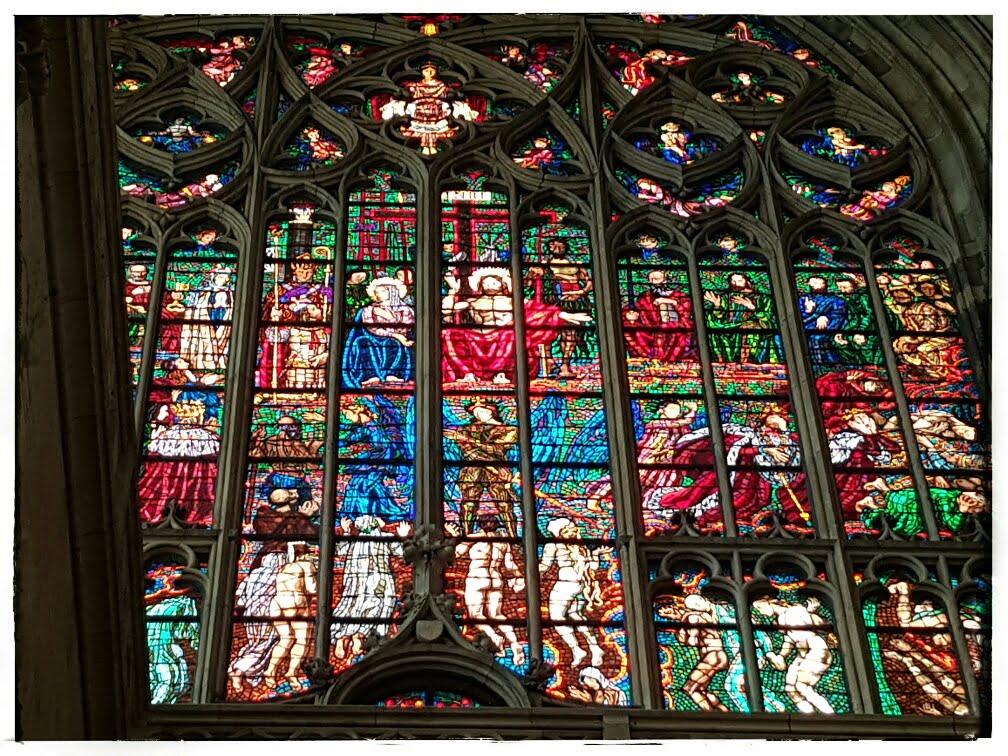

The third stop on our castle tour was the much trafficked St. Vitus Cathedral (i.e., Katedrala sv. Vita).

The rose window.

The organ.

Detail on some columns. Not something of note for most.

The light: As SS pointed out, the windows on the laity are clear, casting a blue, or cold light. The yellow windows close to the pulpit cast a gold light on the clergy.

The stained glass, while beautiful, is far from original.

As you leave the cathedral you pass through a chapel dedicated to Wenceslas (Duke of Bohemia, later assassinated, sainted, posthumously declared king and became, yes, the Wenceslas of the carol).

The crown of Wenceslas; sapphire, aquamarine, pearls, and other gems.

The next stop on the whirlwind tour was to the history of the palace. This is, geographically, part of the palace, in the rooms of the members of the court.

The red Prada shoes of Benedict XVI were much in the news. But these twelfth century Papal slippers show it’s always been vogue to be vogue.

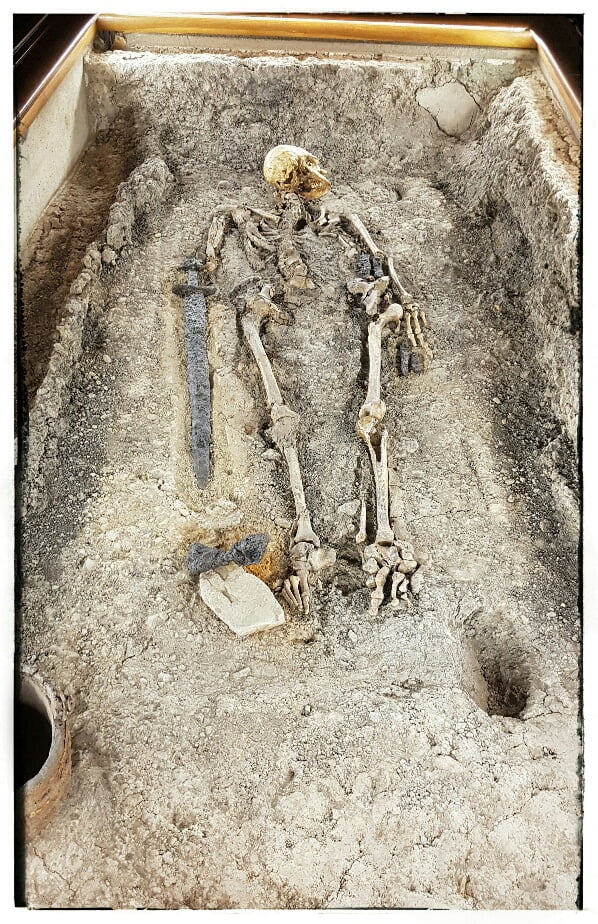

The ruins in this area date to the Pleistocene (e.g., woolly mammoths, of which there are some remains on display). Human remains to 3200 BC. This skeleton is a taste of the medieval ossuary.

Prince Victor Amadeus of Savoy at the age of eleven.

There is a book on the invention of childhood. It’s a provocative idea for which there is interesting historical precedent. The pictures show that for centuries children were adults: They were dressed in adult clothes and painted, in portraits, as adults.

I kid you not: This is a portrait of a four year old.

Last stop on the castle tour proper was the Golden Lane, a rabbit warren of small rooms and narrow halls. The Golden Lane got its name because these tiny hovels allowed goldsmiths to avoid guild dues in town. Franz Kafka even lived here once.

One large section was dedicated to armor, shields and weaponry.

A perfect fit for Robert Downey Jr.

My, what a big piece. Of metal.

The Stig wore this on Top Gear.

Instruments of torture.

The “lane” had many small houses, some depicting the workers who had a place to stay next to the castle, some more contemporary.

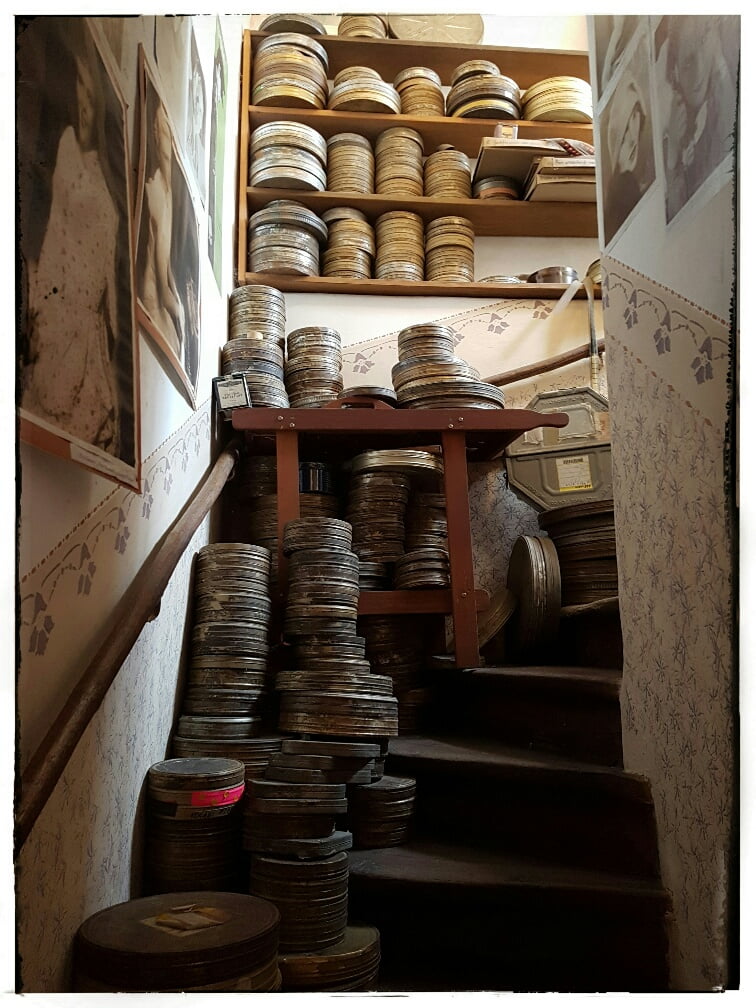

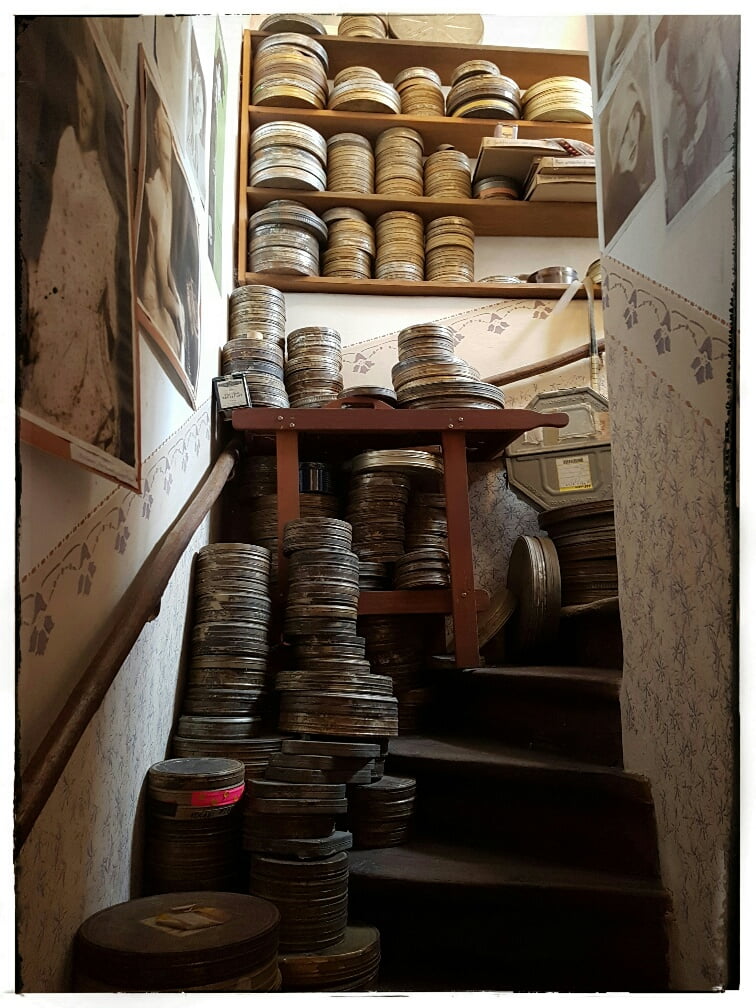

This is a pic of where Josef Kazda lived during the second world war. Kazda didn’t hide Jews in his attic nor was he a liberal, communist or anarchist in the resistance. But he still did something special: He collected and archived hundreds of Czech films during the war (the Cezch film industry had flourished pre-WWII). He hid them in his tiny home in the Golden Lane.

It was well into lunch by now. Rather than spend a long time wandering around for a place, we had soup and mezze on a terrace in one corner of the grounds.

The cafe was actually part of a private palace, the only privately owned area of the grounds. It required a separate admission which, I supposed, was a deterrent to the masses of tourists. We decided to have a look after lunch.

The cafe was actually part of a private palace, the only privately owned area of the grounds. It required a separate admission which, I supposed, was a deterrent to the masses of tourists. We decided to have a look after lunch.

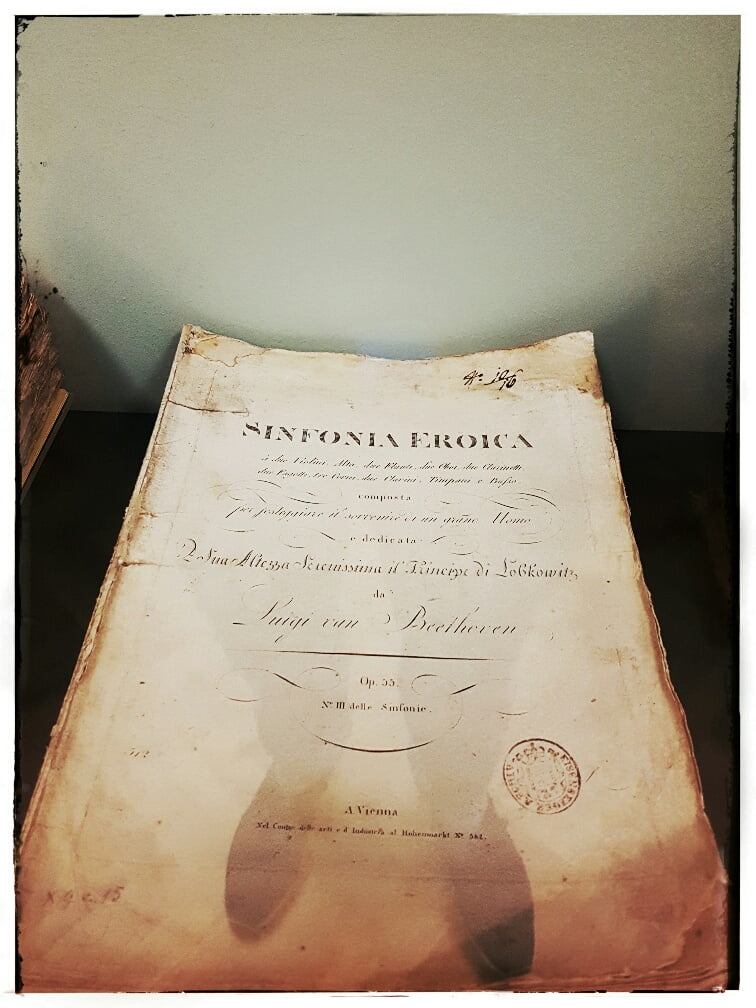

The collection was a mix of interesting and blow-away. The picture above is an original version of Beethoven’s Eroica.

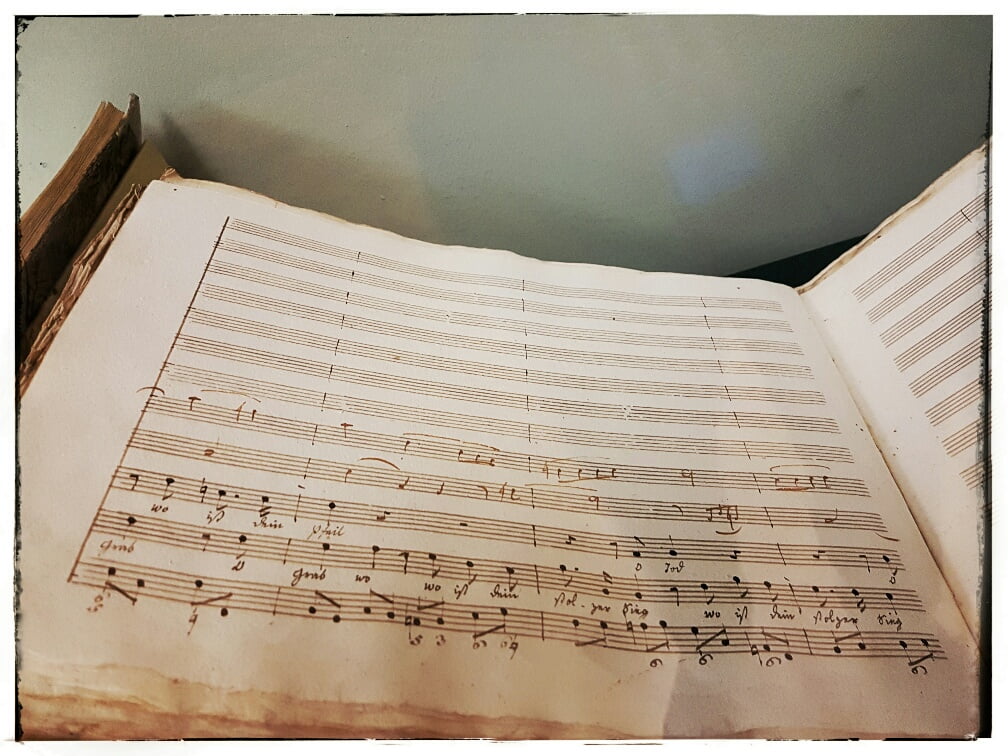

This picture is Mozart’s hand written arrangement for Handel’s Messiah.

Both were in the “music room” which housed a huge display of antiquated fine instruments.

There were definitely less captivating rooms, such as the “bird room”…

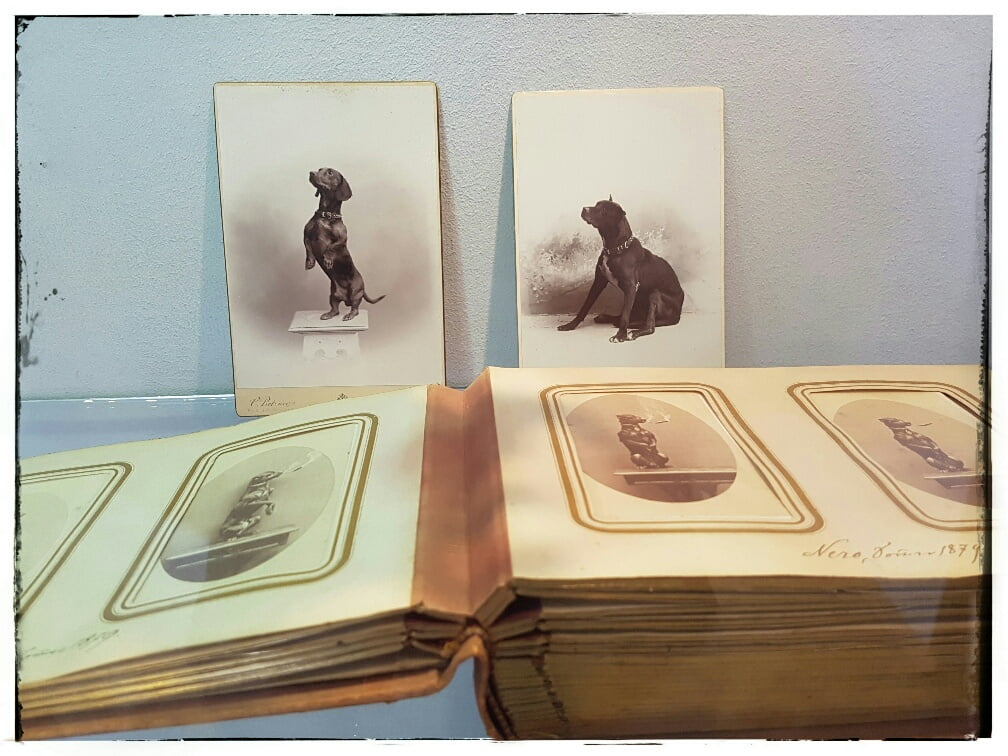

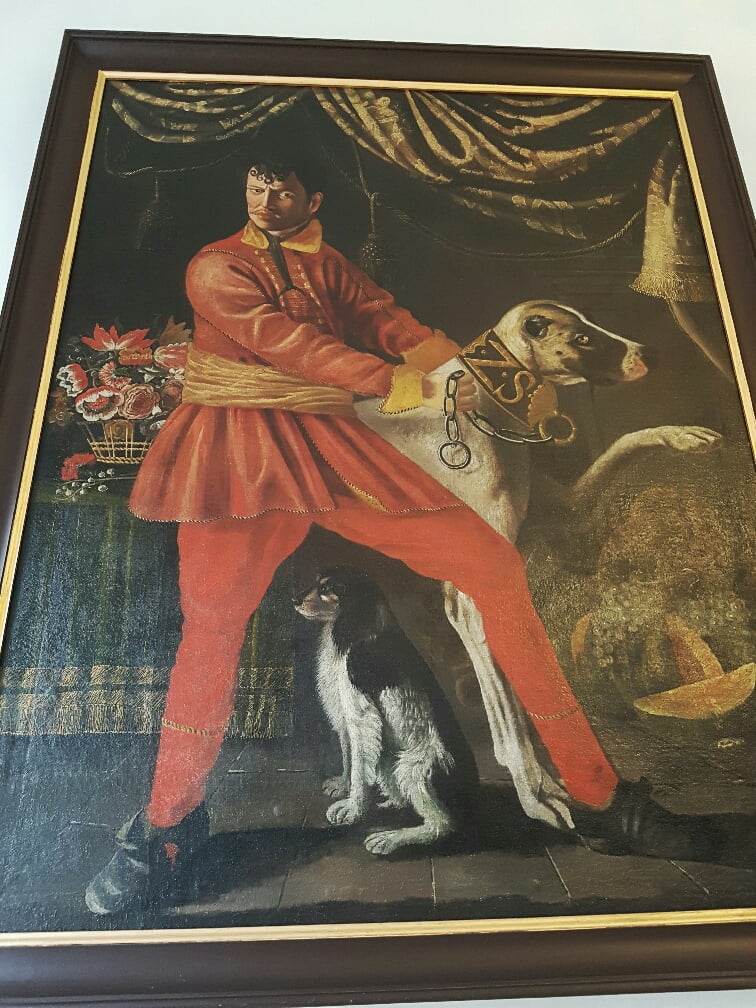

…and the “dog room” to name a few. The back story of the Lobkowicz Museum is that the family was extremely wealthy, with castles across Bohemia. They lost everything first to the Nazis, which sent the scion of the family to London, then the US. They got everything back after WWII only to lose it to the communists. In the 1990s, under Havel, they recouped a lot of their belongings. So this is either a good news story, whereby some incredibly rich people reclaimed their art and put it on display for the public, or a mistake of the state to cede such valuable treasures to a family who reaped the rewards of a feudal system. Your call.

There was a stunningly restored 1700 grandfather clock keeping perfect time made by the inventor of the repeating watch and the portable barometer.

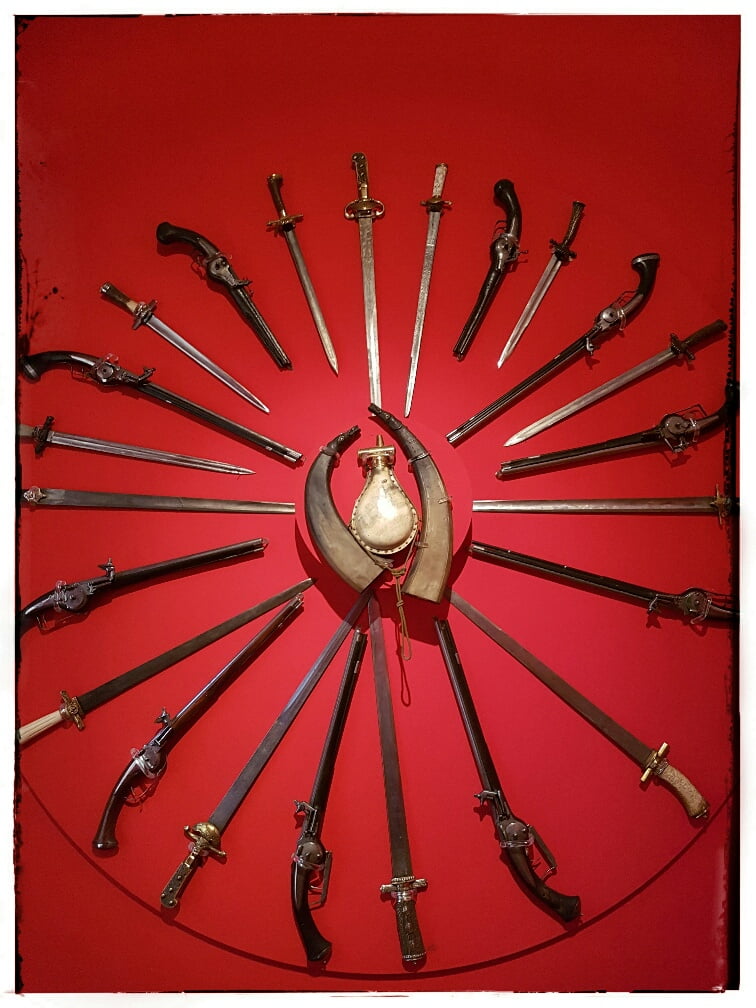

The gun room was an exceptionally well-displayed collection. Particularly compared to the state funded castle displays. So another argument, perhaps, for private ownership.

There are a couple of absolutely over the top amazing treasures. The first is a Bruegel who was the first person to paint pre-industrial rural life not as a backdrop for a Biblical scene but as a reality of daily life.

This crappy picture which does no justice is Haymaking from 1565.

In the next room, it gets even better with not one but two Canaletto’s of London from 1746-8.

These two details of Lord Mayor’s Day, on the Thames, are an unbelievable record of London in 1750. The family has a Rubens to boot–but you have to visit one of their castles in the country!

There was a special balcony with great views of Prague. Cost an extra $7.50 CDN!

So I snapped the pic above, and the pic below, through the window, and saved the money.

After an over the top hour or so in the Lobkowicz, we wandered through the castle gardens, which abut the current presidential palace. They were not as refined or structured as Vienna, but pleasant.

The Belvedere is, apparently, “the finest example of the Renaissance style of architecture outside of Italy” although the Communist era gave it little love…

There were good views back to the cathedral.

We stopped briefly to listen to a woman in the garden with “tame” falcons and owls

We decided to walk back to the hotel the long way, first “backwards” to Loreto Square where the church was under scaffolding, then down to the river.

Along one of the many narrow, winding cobblestone streets we stumbled across Tycho De Brahe’s home.

We had seen the Senate garden from a distance, which looked interesting.

But the “sculptured” grotto we’d seen at a distance was something of a failed attempt up close.

For dinner we left the centre, and tourist area, and went “deep east” into a working class neighbourhood (Karlin) for a superb meal at a place called Nenjen bistro.

Back at the hotel nearly night night we hear some very loud noise and weren’t sure whether to panic. We both looked outside: There was, somewhere, nearby, fireworks. We watched about 10 minutes before calling it a night.